Let me start by saying that this isn’t my code. It’s not my rules to skiing and riding. And it’s certainly not something I invented nor is it just my opinion.

The following is a set of guidelines, with some fluff, that were developed to help everyone on the hill ski and ride safely, and generally have a good time. Would it really be worth sharing a hill with people who have no comprehension of the courtesies and considerations involved with sliding? Let’s put it this way: would you want to drive on roads where there were no rules and no guidelines? No lines on the road and no traffic lights?

I think we can agree that the scenario described above would be rather dangerous for driving, and the same goes for skiing and riding. You share the mountain with other people, so we all need a common set of rules to follow. It’s not just for your enjoyment, but your safety, and it’s your responsibility to know it. So, without further ado, I present: The Skier’s/Rider’s Code.

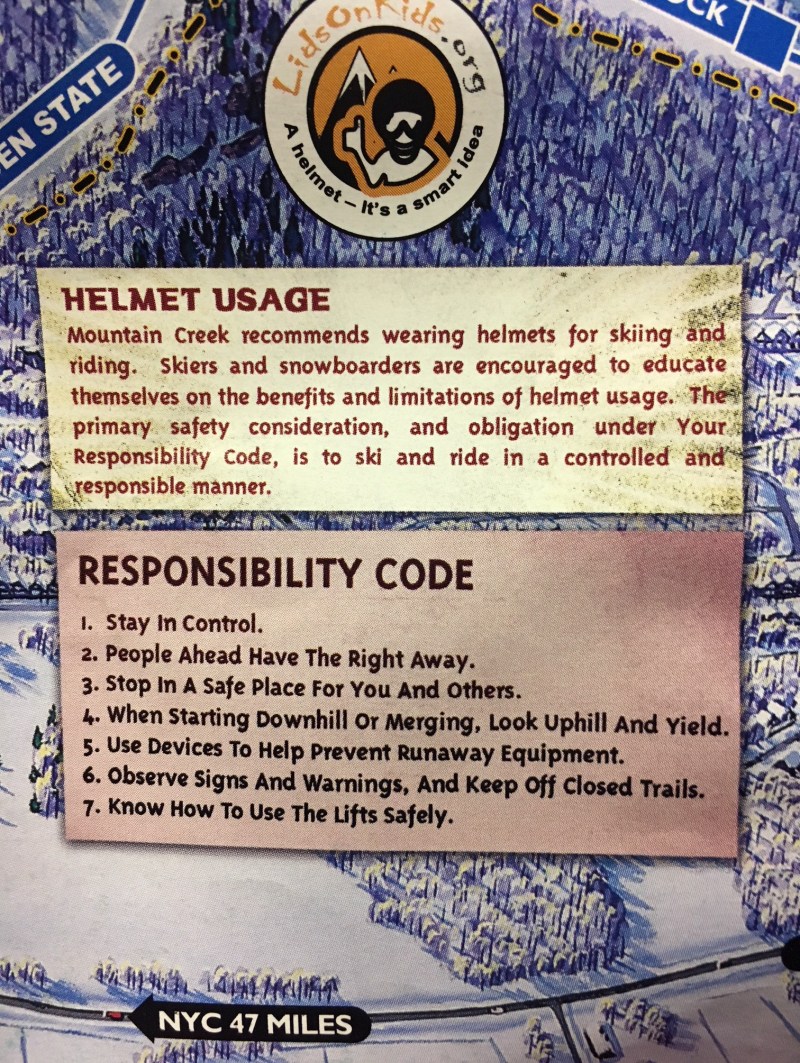

Rule 1

Always stay in control and be able to stop or avoid other people or objects.

Why? Because unexpected terrain, obstacles, and people can appear on the hill. If you are in control, it is more likely that you will be able to avoid obstacles and maneuver safely, saving yourself, and possibly others, a trip down the hill with Ski Patrol. At our Patrol we suggest you only ski or ride at 70-80% (at the most) of your ability as for whatever reason you may need that extra 20% to avoid something. On the other hand, if you ski or ride at 100% of your ability, making maneuvers is that much harder, and stopping takes a lot longer.

Rule 2

People ahead of you have the right of way. It is your responsibility to avoid them.

This one is something people argue with me about more than any of the others. People are prone to making excuses as to why the person IN FRONT of them was at fault for turning, or using more of the hill than they’d expected. Put simply, this is ridiculous. Think about it like this: you have to look the way you are skiing or riding, which is downhill. If you are expected to look downhill, how can you also be looking behind you to make sure you aren’t in the way of others? Well, you can’t. So, it is your responsibility while someone is INFRONT/downhill of you, AND as you pass them, to make sure that you don’t hit them. It’s their responsibility to make sure they don’t hit you when you are downhill of them too, but giving each other enough space to turn one way or the other is essential, because you don’t know their skiing ability, their intentions on the hill, or their plans to turn or stop.

I’ve even had altercations with fellow instructors telling me I’m wrong about this and that there are ”unwritten rules” that invalidate this. Michael, if you are reading this, I am absolutely referring to you. Yelling “ON YOUR RIGHT” or “ON YOUR LEFT” does not take the place of this rule. Is it good to let your fellow skiers and riders know where you are? Yes. Is it particularly useful to let others know where you are if you are on a tight trail and would like to pass? Absolutely. There’s really nothing wrong with doing this, but it DOES NOT substitute or take the place of people ahead of you having the right of way, and you being responsible for avoiding them, including when you pass them. It is not their responsibility to move out of the way when you yell “on your left”. Okay, moving on.

Rule 3

You must not stop where you obstruct a trail or are not visible from above.

This is one that almost all of us are guilty of doing at some point. Whether we know it or not, it happens. And it happens more often when we’re visiting a mountain. Not knowing where the rises and dips are, where the next trailhead may be, and just generally being unfamiliar with the mountain. This is no excuse, however, because of the problems we create when we obstruct a trail or make ourselves not visible from above. When we do these two things, we cause hazards that may force other skiers to make unnecessary, potentially high-risk maneuvers to avoid us. So we put ourselves in danger, and we force other skiers and riders to put themselves in danger. This is also seen in terrain parks on the backside of landing zones and jumps where it is next to near impossible for a skier or rider to see someone downhill of them over the crest of a jump.

When you stop on a trail, do it at the side where you are out of everyone’s way, and be aware of the rises on the hill to make sure you are not on the backside of one. It’s for your safety, and it’s for ours.

Rule 4

Whenever starting downhill or merging into a trail, look uphill and yield to others.

I’ll use the car analogy again because that seems to be an easy way of explaining this one. When you’re about to make a turn on to a road, you make sure that there are no other cars coming first. Well the same goes here. If skiers and riders are coming down the hill and you are stopped on the side of the trail (the correct place to stop on a trail), when you start moving again you are re-joining the flow of traffic. It is your responsibility to ensure that when you rejoin the flow, you don’t begin moving when there are people passing you or about to pass you, as this would be the same as moving into the path of an oncoming car.

Rule 5

Always use devices to help prevent runaway equipment.

What does this really mean? Your skis have brakes on them for when you unclip from your binding. These are important parts to the ski as they prevent the ski from running down the hill without you. If you do decide to take the brakes off them, please use straps that clip to your ski boot so that the skis don’t accidentally go freeriding on their own. For snowboarders, you can use a strap to prevent your board running away, or you can make sure you maintain a firm grip of your board until you have your front foot strapped in. The amount of boards we see coasting down the hill with no one on them is far too many! It’s an easy one to fix.

Rule 6

Observe all posted signs and warnings. Keep off closed trails and out of closed areas.

This ranges from slow signs in high-traffic areas and at trail-crossings, to ribbons and ropes across closed trail-heads and specific no-skiing areas. There are good reasons for all of these signs. They’re not just there to stop you from having fun.

Slow, Variable Terrain, Thin Cover, Caution: Cliff. All of these signs post some kind of warning to you about something ahead. Important, but rarely observed. Going slow doesn’t mean you can’t continue skiing, it just means that you should slow yourself down because this area of the mountain could have:

- High traffic flow

- A trail crossing (blind or seen)

- Beginner skiers on it

- A sharp decline after it

These are just a few of the things the slow sign could be warning you about. Observing it won’t do you any harm, whereas ignoring it could. The same goes for variable terrain and thin cover signage. These are warning you about possible ice, rocks, bumps, slush, crud, etc. It is the Patrol warning you about the terrain ahead and letting you know that you may find unexpected things ahead of you.

Caution: cliff. If you don’t see the importance of this one, maybe you were destined to ignore it.

Rule 7

Prior to using any lift, you must have the knowledge and ability to load, ride, and unload safely.

Why? Because getting on and off the lift can be dangerous. A chair catching you as you’re skiing or riding to the loading zone may result in a bad day. Falling when getting off the chair and being hit by it, or hitting hard on ice may result in a bad day. Basically, any combination of factors that end with you below a chair or being hit by it may result in having a bad day. All it takes is the wrong twist at your joints or falling poorly to end your season (think ACL tears, dislocated shoulders, broken wrists). And that’s not even considering that any time one of these things happen, the lift attendant may need to stop the lift. For any of you who have ridden a chair lift before, this can become rather frustrating when it happens over and over.

How can you ensure you get off the chairlift safely?

- Make sure you don’t have any loose clothing that will keep you attached to the chair when you try to make your exit

- Sit forward as you approach the unloading zone

- Stand up once your skis or board touch the unloading zone, keeping weight over your skis or front foot, and pushing away from the chair if need be

- Ride straight down the unloading zone and away from it until you are sure that turning won’t result in you or another person falling

Now, riding the chairlift isn’t usually an issue once you are on, but there are those who fall off, either at the start, middle, or end. To ride a chairlift, just sit down and stay sitting back until the unloading zone (steps for this mentioned above). If you have a backpack, take it off and hold it in front of you. Don’t fiddle with the bindings on your board, don’t reach for your skis, and keep a hold of your poles so they don’t fall off the chairlift. The less you fidget with things and take things off or out like gloves, phones, and GoPros, the less likely things are to fall from the chair and get lost. If something does fall, don’t reach for it, just remember which lift tower it was nearest (they’re numbered) and go get whatever you lost if it’s accessible.

There’s a lot of simple things you can do to stay safe on a chairlift, and most of them involve you, not the chairlift. So talk to the person next to you if you like, or stare straight ahead in awkward silence, but know the risks you are taking by messing around with all of your gadgets/toys/equipment while you’re up high in the sky.

This list of rules is a basic set of guidelines for you to know and practice. Be safety conscious out there, and there is no substitute for common sense, thinking practically, and personal awareness. If it seems unsafe, you’re probably right.

A few more tips before you go:

Wear A Helmet

- It could save your life. You may not be reckless, but others may well be.

- Don’t let “it’ll ruin my hair” be your excuse not to wear a helmet. Would you rather have good hair and be brain dead or just take a shower after you get home from skiing or riding?

- “It’s uncomfortable.” Find a helmet that is comfortable. There are TONS of them with different fits, padding, and styles.

- It could stop serious injury even when you aren’t on your skis. Ski boots have bad traction on wet stone and cement, and skis and boards can have incredibly sharp edges. Trust me, I know.

Look Before You Leap

It seems obvious to me, but I’ve seen far too many people miscalculate jumps or not even bother to calculate the size of the jump or what the landing looks like. Plain as day, look before you leap, whether it’s park jumps, rails, cliffs, etc. Knowing what you’re getting into is far better than finding out part way through the air that you’ve made a bad judgement call, or half way down a mountainside and realising you’re in over your head.

“The videos make it look so easy though.”

When you watch a video clip, you’re seeing just that: a clip. You’re not seeing the times the athlete did a park-lap run-through to check out features and jumps. You’re not seeing the planning and research the person did before selecting their route down the mountainside. You’re not seeing the speed-checks and the times they decided not to hit it. You’re not seeing the times they failed and times it didn’t work out. Watch some b-roll footage, some wipe outs, and some full-length ski and snowboarding movies and you’ll see what I mean. This leads me into my final tip for you.

If You Don’t Know, Don’t Go

Made famous on Big Red at Jackson Hole, this phrase says it all. Particularly in the backcountry it’s important to know what you’re doing, where you’re doing it, how your equipment works should you need to use it, and who you’re doing it with.

- If you don’t know your gear, don’t go.

- If you don’t know the avy conditions, don’t go.

- If you don’t know your partner’s riding ability, don’t go.

- If you don’t know where you’re going to end up, don’t go.

It’s really simple, and both Jackson Hole Mountain Resort and Teton County Search and Rescue are huge advocates of this easy-to-remember preventative strategy. “If you don’t know, don’t go” applies to many aspects of skiing and riding in-bounds too, so don’t just save your wise decisions for beyond the boundary tape. You can read more about this philosophy here.

There are some other great tools out there to help you stay safe and be safety conscious. If you would like to learn more checkout:

- The National Ski Areas Association safety video

- The 10 FIS Rules for the Conduct of Skiers and Snowboarders

- Killington’s Mountain Safety Guide

- Winter Backcountry Risk and Safety in Jackson Hole

- The Colorado Ski Safety Act